Nikos Kazantzakis (1883-1957), Panait Istrati (1884-1935)

Kazantzakis and Istrati met during the former’s trip to the Soviet Union in November 1927. Both were social reform enthousiasts, but their different way of seeing it tore them apart.Kazantzakis was too metaphysical, and Istrati took a materialistic view that his friend couldn’t cope with.

A second meeting the following year just widened the gap between them. They continued corresponding, however, and “Don Quixote” was written for Istrati.

Istrati visited Greece shortly after he had met Kazantzakis, to give a lecture on the Bolshevik Revolution, which caused a demonstration in Athens, and resulted in his deportation. During his stay, he visited left-wing patients with tuberculosis in an Athens hospital, being himself a patient, which didn’t go down too well with authorities. He died sick and alone in Bucarest.

Kazantzakis outlived him by 22 years. He mentions Istrati repeatedly in his works.

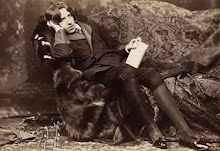

Here is an excerpt chosen and translated by Costas Papageorgiou, to match the photo of the friends in Athens.

"We entered a restaurant, we sat down. He then took a bottle of oil he wore around his neck as a charm and poured it in his food. Afterwards he took a box of pepper out if his vest pocket and threw in his rich meat soup.

-Oil and pepper, he said licking his lips. Just like Braila!

We dag in our food with an appetite. One by one, Istrati recalled the greek words he knew, clapping his hands like a child, crying:

words he knew, clapping his hands like a child, crying:

-Welcome! Welcome back. How have you been?

He kept an eye on his watch. All of a sudden he stood up.

-It’s time to go.

He called for the waiter; he took four bottles of fine Armenian wine, filled his coat pockets with small packs of desserts, overfilled his tobacco box with cigarettes and off we went."

Nikos Kazantakis, A report to Greco

Μπήκαμε σ’ ένα ρεστοράν, καθίσαμε˙ έβγαλε από το λαιμό του, όπου είχε κρεμασμένο, σαν χαϊμαλί, ένα μποτιλάκι λάδι και περέχυσε το φαΐ του. ύστερα έβγαλε από την τσέπη του γιλέκου του ένα κουτάκι πιπέρι κι έριξε μπόλικο στην πηχτή κρεατόσουπα.[…] Φάγαμε με κέφι˙ ο Ιστράτη σιγά σιγά θυμόταν τα ελληνικά του και κάθε τόσο που ανέβαινε από τη μνήμη του μια λέξη χτυπούσε τα παλαμάκια σαν παιδί:

-Καλώς τη! Φώναζε σε κάθε λέξη˙ καλώς τη! Τι μου γίνεσαι;

Νίκος Καζαντζάκης, Αναφορά στον Γκρέκο.

-Oil and pepper, he said licking his lips. Just like Braila!

We dag in our food with an appetite. One by one, Istrati recalled the greek

words he knew, clapping his hands like a child, crying:

words he knew, clapping his hands like a child, crying:-Welcome! Welcome back. How have you been?

He kept an eye on his watch. All of a sudden he stood up.

-It’s time to go.

He called for the waiter; he took four bottles of fine Armenian wine, filled his coat pockets with small packs of desserts, overfilled his tobacco box with cigarettes and off we went."

Nikos Kazantakis, A report to Greco

Μπήκαμε σ’ ένα ρεστοράν, καθίσαμε˙ έβγαλε από το λαιμό του, όπου είχε κρεμασμένο, σαν χαϊμαλί, ένα μποτιλάκι λάδι και περέχυσε το φαΐ του. ύστερα έβγαλε από την τσέπη του γιλέκου του ένα κουτάκι πιπέρι κι έριξε μπόλικο στην πηχτή κρεατόσουπα.[…] Φάγαμε με κέφι˙ ο Ιστράτη σιγά σιγά θυμόταν τα ελληνικά του και κάθε τόσο που ανέβαινε από τη μνήμη του μια λέξη χτυπούσε τα παλαμάκια σαν παιδί:

-Καλώς τη! Φώναζε σε κάθε λέξη˙ καλώς τη! Τι μου γίνεσαι;

Νίκος Καζαντζάκης, Αναφορά στον Γκρέκο.

2 comments:

Should we look at the Romanian folklore, a faithful mirror of the folk mindset, we will note that Romanians had always empathized with the Greeks, considering them friends with whom they shared religion and often the same hardships. A comparative study of mentalities could reveal striking similarities and affinities between the two nations. Greek literary works gained wide recognition on Romanian soil and became popular reading.

Furthermore, mention should be made of the fact that the beginnings of modern Romanian literature are closely intertwined with those of neo-Hellenic literature. The first generation of 19th century poets formed under the influence of the Phanariot Athanasios Hristopoulos. Most Romanian intellectuals in the former half of the 19th century could speak Greek (as alumni of the Princely Academies or of the many Greek private schools) and made their literary debut with translations from Neo-Greek.

The most direct means of dialogue between the two cultures is provided by translations. No wonder therefore that in point of translations from neo-Greek, Romania holds one of the leading positions in Europe. The Romanian public has familiarized with neo-Greek literature through translations since the 17th century.

Daca ne uităm la folclorul românesc, o oglindă fidelă a modului in care se construieste un popor, vom nota că românii au avut întotdeauna relatii faine cu grecii, considerându-i prietenii cu care au împărtăşit atat religia dar de multe ori si greutatile. Un studiu comparativ al mentalităţilor ar putea dezvălui şi afinitati, izbitoare asemănări între cele două naţiuni. operele literare in limba greaca au dobândit o mare recunoaştere si pe teritoriul românesc a devenit o lectură mai mult decat populara.

Mai mult, ar trebui să se menţioneze faptul că începuturile literaturii moderne a românilor sunt strâns legate cu cele din literatura de neo-elena. Prima generaţie de poeţi din secolul 19 s-au format sub influenţa Phanariot Athanasios Hristopoulos. Cei mai mulţi intelectuali români, în fosta jumătate a secolului al 19-lea, puteau vorbi greacă (ca absolventii de la Academiile domnesti sau de la mai multe şcoli private de greacă) şi si-au făcut debutul literar cu traduceri din neo-greacă.

Cel mai direct mijloc de dialog între cele două culturi este furnizat de traduceri. Nu e de mirare, prin urmare, că, în ce priveste numarul de traduceri din neo-greacă, România deţine una din pozitiile de top în Europa.Românii sunt familiarizati cu literatura neo-greacă, prin traduceri, inca din secolul al 17-lea.

zoe

Post a Comment